On Nov. 15, 2021, Russia destroyed one of its own old satellites using a missile launched from the surface of the Earth, creating a massive debris cloud that threatens many space assets, including astronauts onboard the International Space Station. This happened only two weeks after the United Nations General Assembly First Committee formally recognized the vital role that space and space assets play in international efforts to better the human experience – and the risks military activities in space pose to those goals.

The U.N. First Committee deals with disarmament, global challenges and threats to peace that affect the international community. On Nov. 1, it approved a resolution that creates an open-ended working group. The goals of the group are to assess current and future threats to space operations, determine when behavior may be considered irresponsible, “make recommendations on possible norms, rules and principles of responsible behaviors,” and “contribute to the negotiation of legally binding instruments” – including a treaty to prevent “an arms race in space.”

We are two space policy experts with specialties in space law and the business of commercial space. We are also the president and vice president at the National Space Society, a nonprofit space advocacy group. It is refreshing to see the U.N. acknowledge the harsh reality that peace in space remains uncomfortably tenuous. This timely resolution has been approved as activities in space become ever more important and – as shown by the Russian test – tensions continue to rise.

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty

Outer space is far from a lawless vacuum.

Activities in space are governed by the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which is currently ratified by 111 nations. The treaty was negotiated in the shadow of the Cold War when only two nations – the Soviet Union and the U.S. – had spacefaring capabilities.

While the Outer Space Treaty offers broad principles to guide the activities of nations, it does not offer detailed “rules of the road.” Essentially, the treaty assures freedom of exploration and use of space to all humankind. There are just two caveats to this, and multiple gaps immediately present themselves.

The first caveat states that the Moon and other celestial bodies must be used exclusively for peaceful purposes. It omits the rest of space in this blanket prohibition. The only guidance offered in this respect is found in the treaty’s preamble, which recognizes a “common interest” in the “progress of the exploration and use of space for peaceful purposes.” The second caveat says that those conducting activities in space must do so with “due regard to the corresponding interests of all other States Parties to the Treaty.”

A major problem arises from the fact that the treaty does not offer clear definitions for either “peaceful purposes” or “due regard.”

While the Outer Space Treaty does specifically prohibit placing nuclear weapons or weapons of mass destruction anywhere in space, it does not prohibit the use of conventional weapons in space or the use of ground-based weapons against assets in space. Finally, it is also unclear if some weapons – like China’s new nuclear capable partial-orbit hypersonic missile – should fall under the treaty’s ban.

The vague military limitations built into the treaty leave more than enough room for interpretation to result in conflict.

Space is militarized, conflict is possible

Space has been used for military purposes since Germany’s first V2 rocket launch in 1942.

Many early satellites, GPS technology, a Soviet Space Station and even NASA’s space shuttle were all either explicitly developed for or have been used for military purposes.

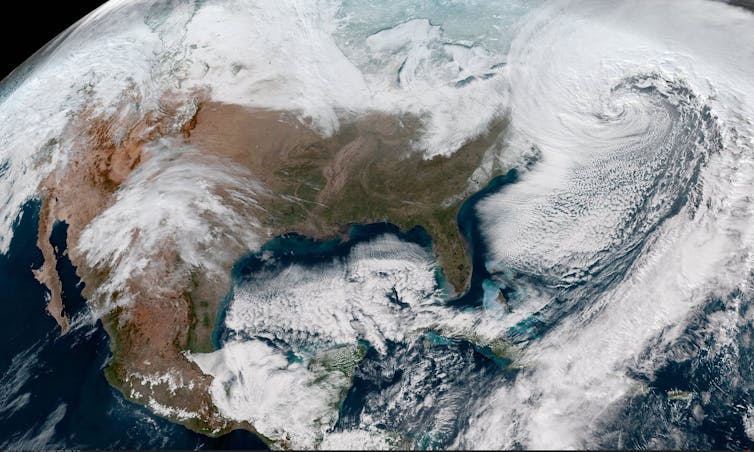

With increasing commercialization, the lines between military and civilian uses of space are less blurry. Most people are able to identify terrestrial benefits of satellites like weather forecasts, climate monitoring and internet connectivity but are unaware that they also increase agricultural yields and monitor human rights violations. The rush to develop a new space economy based on activities in and around Earth and the Moon suggests that humanity’s economic dependence on space will only increase.

However, satellites that provide terrestrial benefits could or already do serve military functions as well. We are forced to conclude that the lines between military and civilian uses remain sufficiently indistinct to make a potential conflict more likely than not. Growing commercial operations will also provide opportunities for disputes over operational zones to provoke governmental military responses.

Military testing

While there has not yet been any direct military conflict in space, there has been an escalation of efforts by nations to prove their military prowess in and around space. Russia’s test is only the most recent example. In 2007, China tested an anti-satellite weapon and created an enormous debris cloud that is still causing problems. The International Space Station had to dodge a piece from that Chinese test as recently as Nov. 10, 2021.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]Similar demonstrations by the U.S. and India were far less destructive in terms of creating debris, but they were no more welcomed by the international community.

The new U.N. resolution is important because it sets in motion the development of new norms, rules and principles of responsible behavior. Properly executed, this could go a long way toward providing the guardrails needed to prevent conflict in space.

From guidelines to enforcement

The U.N. Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space has been addressing space activities since 1959.

However, the remit of the 95-member committee is to promote international cooperation and study legal problems arising from the exploration of outer space. It lacks any ability to enforce the principles and guidelines set forth in the 1967 Outer Space Treaty or even to compel actors into negotiations.

The U.N. resolution from November 2021 requires the newly created working group to meet two times a year in both 2022 and 2023. While this pace of activity is glacial compared with the speed of commercial space development, it is a major step in global space policy.![]()

Michelle L.D. Hanlon, Professor of Air and Space Law, University of Mississippi and Greg Autry, Clinical Professor of Space Leadership, Policy and Business, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.