The answer to whether tiny bacterial lifeforms really do exist in the clouds of Venus could be revealed once-and-for-all by a UK-backed mission.

Over the past five years researchers have detected the presence of two potential biomarkers – the gases phosphine and ammonia – which on Earth can only be produced by biological activity and industrial processes.

Their existence in the Venusian clouds cannot easily be explained by known atmospheric or geological phenomena, so Cardiff University’s Professor Jane Greaves and her team are plotting a way to get to the bottom of it.

Revealing a new mission concept at the Royal Astronomical Society’s National Astronomy Meeting 2025 in Durham, they plan to search and map phosphine, ammonia, and other gases rich in hydrogen that shouldn’t be on Venus.

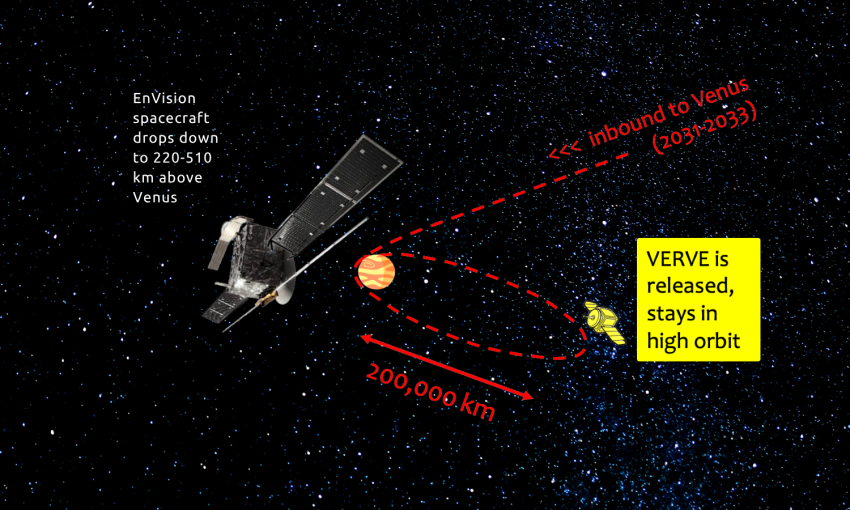

This would involve building a CubeSat-sized probe with a budget of 50 million euros (£43 million) to hitch a ride with the European Space Agency’s EnVision mission – scheduled for 2031. VERVE (the Venus Explorer for Reduced Vapours in the Environment) would then detach on arrival at Venus and carry out an independent survey, while EnVision probes the planet’s atmosphere, surface and interior.

“Our latest data has found more evidence of ammonia on Venus, with the potential for it to exist in the habitable parts of the planet’s clouds,” Professor Greaves said.

“There are no known chemical processes for the production of either ammonia or phosphine, so the only way to know for sure what is responsible for them is to go there.

“The hope is that we can establish whether the gases are abundant or in trace amounts, and whether their source is on the planetary surface, for example in the form of volcanic ejecta.

“Or whether there is something in the atmosphere, potentially microbes that are producing ammonia to neutralise the acid in the Venusian clouds.”

Phosphine was first detected in the Venusian clouds in 2020 but the finding proved controversial because subsequent observations failed to replicate the discovery.

However, that didn’t deter the team of researchers behind the JCMT-Venus project – a long term programme to study the molecular content of the atmosphere of Venus which first involved the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii.

They tracked the phosphine signature over time and found that its detection appeared to follow the planet’s day-night cycle – i.e. it was destroyed by sunlight.

They also established that the abundance of the gas varied with time and position across Venus.

“This may explain some of the apparently contradictory studies and is not a surprise given that many other chemical species, like sulphur dioxide and water, have varying abundances, and may eventually give us clues to how phosphine is produced,” said Dr Dave Clements, of Imperial College London, who is the leader of the JCMT-Venus project.

It was then revealed at last year’s National Astronomy Meeting in Hull that ammonia had also been tentatively detected on Venus. On Earth, this is primarily produced by biological activity and industrial processes.

But there are no known chemical processes or any atmospheric or geological phenomena which can explain its presence on Venus.

Although temperatures on the surface of the planet are around 450C, about 50km (31 miles) up it can range from 30C to 70C, with an atmospheric pressure similar to Earth’s surface.

Under these conditions it would be just about possible for “extremophile” microbes to survive, potentially having remained in the Venusian clouds after emerging during the planet’s more temperate past.

But the only way to know for sure, the JCMT-Venus researchers say, is to send a probe to find out.

New research papers about the latest discoveries are expected to be published later this year.