Humans have taken spiders into space more than once to study the importance of gravity to their web-building. What originally began as a somewhat unsuccessful PR experiment for high school students has yielded the surprising insight that light plays a larger role in arachnid orientation than previously thought.

The spider experiment by the US space agency NASA is a lesson in the frustrating failures and happy accidents that sometimes lead to unexpected research findings. The question was relatively simple: on Earth, spiders build asymmetrical webs with the center displaced towards the upper edge. When resting, spiders sit with their head downwards because they can move towards freshly caught prey faster in the direction of gravity.

But what do arachnids do in zero gravity? In 2008, NASA wanted to inspire middle schools in the US with this experiment. But even though the question was simple, the planning and execution of the experiment in space was extremely challenging. This led to a number of mishaps.

Two specimens from different spider species flew to the International Space Station (ISS) as “arachnauts,” one (Metepeira labyrinthea) as the lead and the other (Larinioides patagiatus) as a reserve in case the first didn’t survive.

The reserve spider escaped

The reserve spider managed to break out of its storage chamber and into the main chamber. The chamber couldn’t be opened for safety reasons, so the extra spider could not be recaptured. The two spiders spun somewhat muddled webs, getting in each other’s way.

And if that were not enough, the flies included as food reproduced more quickly than expected. Over time, their larvae crawled out of the breeding container on the floor of the case into the experimental chamber, and after two weeks covered large parts of the front window. After a month, the spiders could no longer be seen behind all the fly larvae.

This failure long nagged at Paula Cushing of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, who participated in the planning of the spider experiment. When the opportunity for a similar experiment on board the ISS cropped up again in 2011, the researcher got Dr. Samuel Zschokke of the University of Basel involved to prepare and analyze the new attempt. This time, the experiment started with four spiders of the same species (Trichonephila clavipes): two flew to the ISS in separate habitats, two stayed on Earth in separate habitats and were kept and observed under identical conditions as their fellows traveling in space – except that they were exposed to terrestrial gravity.

The females were males

The plan was originally to use four females. But another mishap occurred: the spiders had to be chosen for the experiment as juveniles and it is extremely difficult to determine the sex of juvenile animals. In the course of the experiment, two of the spiders turned out to be males, which differ markedly in body structure and size from females of this species when fully grown. But finally there was a stroke of luck – one of the males was on board the space station, the other on Earth.

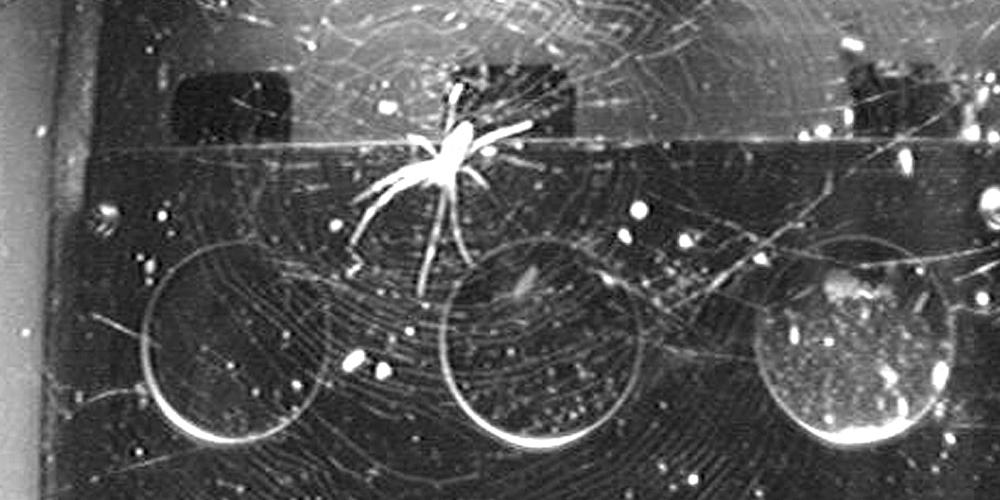

The arachnids spun their webs, dismantled them, and spun new ones. Three cameras in each case took pictures every five minutes. Zschokke, Cushing and Stefanie Countryman of the University of Colorado’s BioServe Space Technologies that oversaw the design and launch of the space flight certified habitats containing the spiders and fruit fly larvae and camera system to the International Space Station analyzed the symmetry of 100 spider webs and the orientation of the spider in the web using about 14,500 images.

It turned out that the webs built in zero gravity were indeed more symmetrical than those spun on Earth. Their center was closer to the middle and the spiders did not always keep their heads downwards. However, the researchers noticed that it made a difference whether the spiders built their webs in lamplight or in the dark. Webs built on the ISS in lamplight were similarly asymmetrical as the terrestrial webs.

Light as a back-up system

“We wouldn’t have guessed that light would play a role in orienting the spiders in space,” says Zschokke, who analyzed the spider experiment and published the results with his colleagues in the journal Science of Nature. “We were very fortunate that the lamps were attached at the top of the chamber and not on various sides. Otherwise, we would not have been able to discover the effect of light on the symmetry of webs in zero gravity.”

Analysis of the pictures also showed that the spiders rested in arbitrary orientations in their webs when the lights were turned off, but oriented themselves away – i.e. downwards – when the lights were on. It seems spiders use light as an additional orientation aid when gravity is absent. Since spiders also build their webs in the dark and can catch prey without light, it had previously been assumed that light plays no role in their orientation.

“That spiders have a back-up system for orientation like this seems surprising, since they have never been exposed to an environment without gravity in the course of their evolution,” says Zschokke. On the other hand, he says, a spider’s sense of position could become confused while it is building its web. The organ responsible for this sense registers the relative position of the front part of the body to the back. During construction of the web, the two body parts are in constant motion, so an additional orientation aid based on the direction of the light is particularly useful.