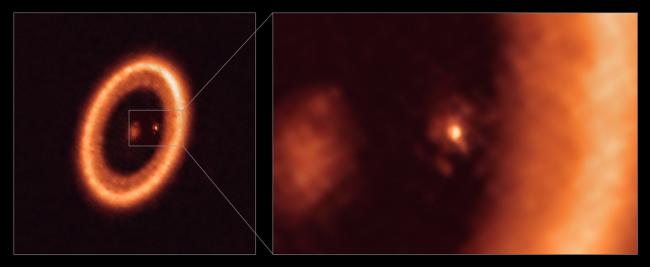

Astronomers at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian have helped detect the clear presence of a moon-forming region around an exoplanet — a planet outside of our Solar System. The new observations, published Thursday in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, may shed light on how moons and planets form in young stellar systems.

The detected region is known as a circumplanetary disk, a ring-shaped area surrounding a planet where moons and other satellites may form. The observed disk surrounds exoplanet PDS 70c, one of two giant, Jupiter-like planets orbiting a star nearly 400 light-years away. Astronomers had found hints of a “moon-forming” disk around this exoplanet before but since they could not clearly tell the disk apart from its surrounding environment, they could not confirm its detection — until now.

“Our work presents a clear detection of a disk in which satellites could be forming,” says Myriam Benisty, a researcher at the University of Grenoble and the University of Chile who led the research using the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array (ALMA). “Our ALMA observations were obtained at such exquisite resolution that we could clearly identify that the disk is associated with the planet and we are able to constrain its size for the first time.”

With the help of ALMA, Benisty and the team found the disk diameter is comparable to the Sun-to-Earth distance and has enough mass to form up to three satellites the size of the Moon.

“We used the millimeter emission from cool dust grains to estimate how much mass is in the disk and therefore, the potential reservoir for forming a satellite system around PDS 70c,” says Sean Andrews, a study co-author and astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics (CfA).

The results are key to finding out how moons arise.

Planets form in dusty disks around young stars, carving out cavities as they gobble up material from this circumstellar disc to grow. In this process, a planet can acquire its own circumplanetary disk, which contributes to the growth of the planet by regulating the amount of material falling onto it. At the same time, the gas and dust in the circumplanetary disk can come together into progressively larger bodies through multiple collisions, ultimately leading to the birth of moons.

But astronomers do not yet fully understand the details of these processes. “In short, it is still unclear when, where, and how planets and moons form,” explains ESO Research Fellow Stefano Facchini, also involved in the research.

“More than 4,000 exoplanets have been found until now, but all of them were detected in mature systems. PDS 70b and PDS 70c, which form a system reminiscent of the Jupiter-Saturn pair, are the only two exoplanets detected so far that are still in the process of being formed,” explains Miriam Keppler, researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany and one of the co-authors of the study.

“This system therefore offers us a unique opportunity to observe and study the processes of planet and satellite formation,” Facchini adds.

PDS 70b and PDS 70c, the two planets making up the system, were first discovered using ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) in 2018 and 2019 respectively, and their unique nature means they have been observed with other telescopes and instruments many times since.

These latest high resolution ALMA observations have now allowed astronomers to gain further insights into the system. In addition to confirming the detection of the circumplanetary disk around PDS 70c and studying its size and mass, they found that PDS 70b does not show clear evidence of such a disk, indicating that it was starved of dust material from its birth environment by PDS 70c.

An even deeper understanding of the planetary system will be achieved with ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), currently under construction on Cerro Armazones in the Chilean Atacama desert.

“The ELT will be key for this research since, with its much higher resolution, we will be able to map the system in great detail,” says co-author Richard Teague, a co-author and Submillimeter Array (SMA) fellow at the CfA.

In particular, by using the ELT’s Mid-infrared ELT Imager and Spectrograph (METIS), the team will be able to look at the gas motions surrounding PDS 70c to get a full 3D picture of the system.